A Weigh Of Life.

A Weigh of Life

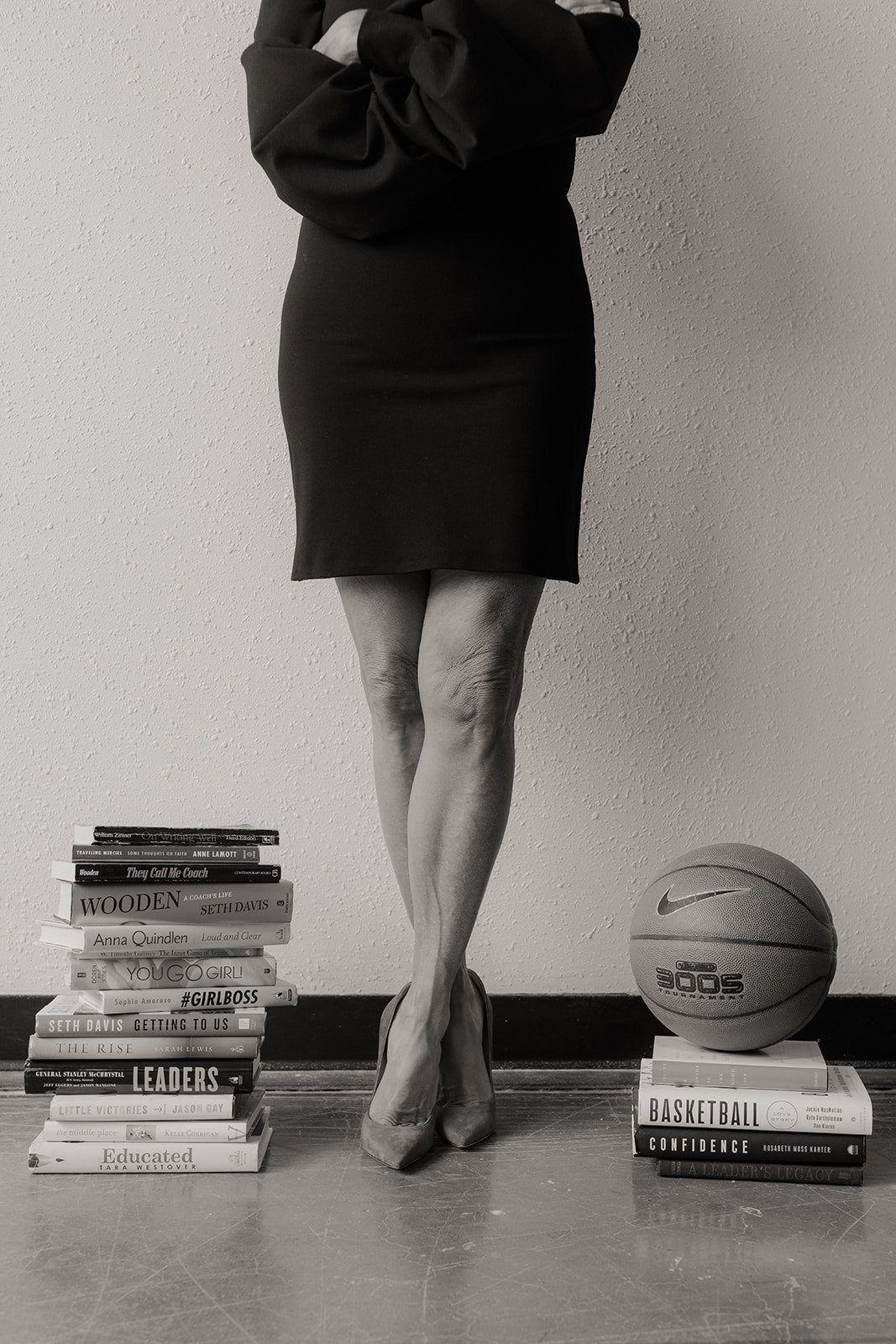

By Sherri Coale

To see historical blogs, please reach out to sherri@sherricoale.com and request the password for the Blog Archive!