To Draw or Not To Draw

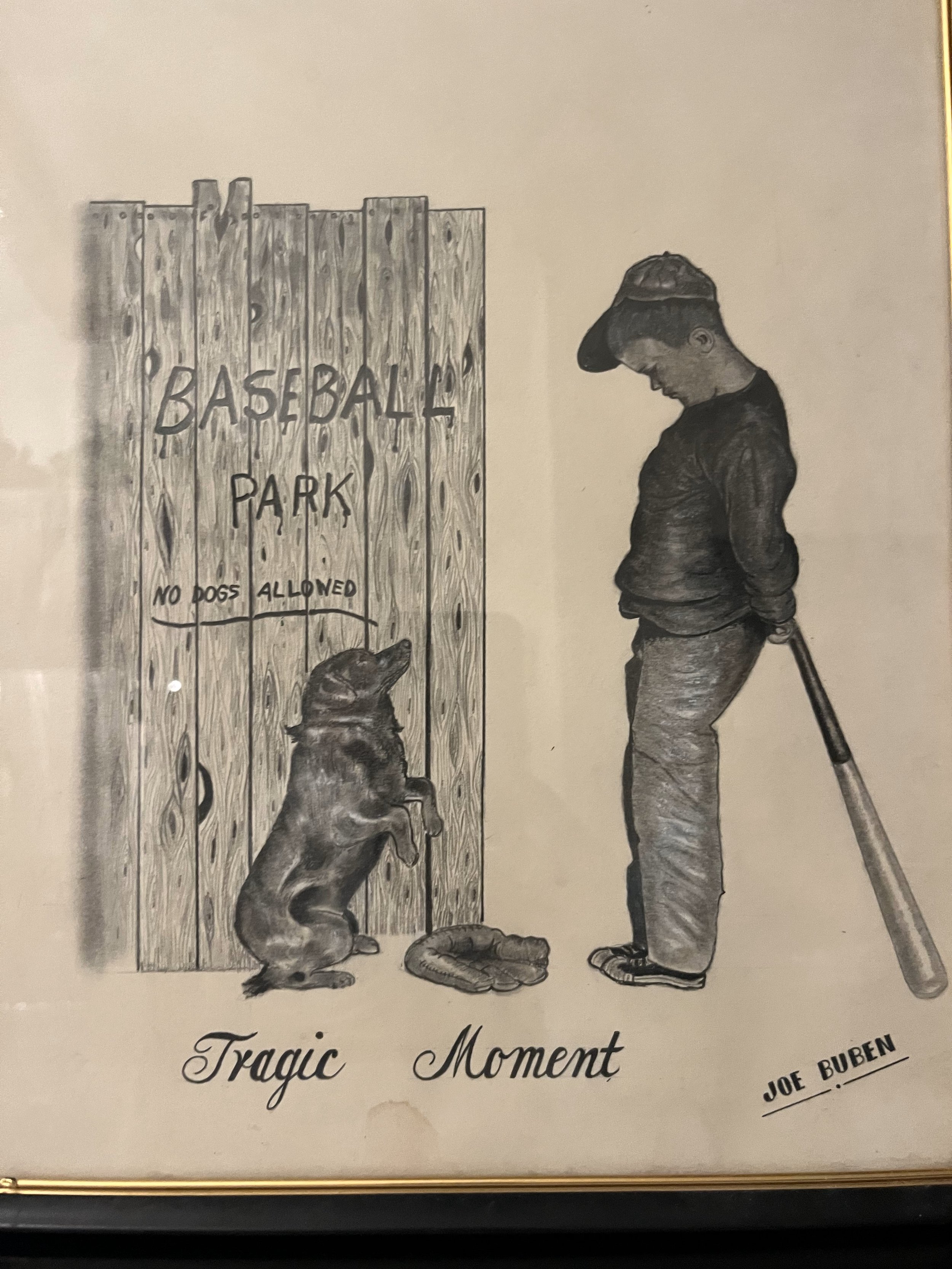

MY DAD COULD REALLY DRAW. He worked in the oil and gas world, but that was just how the bills got paid. On the side, he painted signs for money, as lettering was his sweet spot. Almost every small business in our rural Oklahoma town had Dad’s handiwork on its welcome board. While painting gave him great enjoyment and padded where the ends wouldn’t meet, his passion was a pencil and pad.

Dad drew everything. Funny cartoons, landscapes, birds, a portrait of his parents. The pencil was a magical wand when tucked between the thumb and index finger of his right hand. I used to sit in his lap and tell him things to draw. I never came up with anything he couldn’t make look real, or at least really funny. He was an untrained artisan who had hitchhiked home from college to join the National Guard and find a way to get by. Somewhere along the way, and maybe long before, he discovered he could draw... though I always wondered if he understood how well. I used to try to be just like him with only drippings from his gift.

When I was in the first grade, I entered a contest to make a poster about poison control. I went with a pencil sketch, of course. My game plan was to draw a boy sitting cross-legged with drug vials and pill bottles littered around him. The caption had something to do with keeping medications safely out of the reach of children, but I honestly can’t remember what the contest was about or even why I was in it. I just remember that I won. And that there was a lot of whispering.

Dad had helped me with the concept, the spacing, and the layout of the sketch. I knew how to measure and align and did so with precision, the way I’d watched him do incessantly across the sawhorses in his barn. It was a poster for a silly contest at school, but I attacked it the only way I knew how—with every fiber of my being. It was toil with my tongue hanging out the side of my mouth. The lettering came pretty easily, but I worked and worked and worked at the details of the boy. I vividly remember struggling with the lines of his limbs, in disbelief at how hard it was to draw bent arms and legs. I sketched softly and erased a lot.

When judgment day came, my poster had a big blue ribbon hanging on its corner. I had no idea that’s what happened when your art was picked as the best, or what it would feel like to win. I don’t think I had even thought winning was an option when I entered, so the spoils came from left field, and when they landed in my lap, it felt like I had caught a cloud. I knew immediately that earning wins was something I would always want to do.

My first grade teacher, Mrs. Lucille Hughes, was a legend at Sunset Elementary. She was the golden standard if ever there was one. Mrs. Hughes had back-combed hair and cat-eye glasses that hung from a chain around her neck when they weren’t sitting on her nose. She was Charles in Charge—a printing press for miniature humans who sat up straight and colored neatly inside the lines. She and the plastic ruler she carried made sure of that. Her track record was renowned. I attended holiday parties in her classroom with my Granny when I was three and my brother was in first grade, and everyone I knew had had her as a teacher—she had even taught my mom. When I turned six and was assigned to Mrs. Hughes’s classroom, I thought I’d roped the moon.

A few days after my blue ribbon victory, Mrs. Hughes handed out the morning’s assignments and then motioned for me to join her at the back of the room. There I found a piece of white poster board, a ruler, some pencils, and ample room to work. She seemed a little nervous, and I was very confused. She had some news to break, that much was obvious. The bush she was beating around didn’t hide her very well.

She told me we needed to draw another poster. “Huh?” I’m sure I said. It needed to be just like the one in the contest, “exactly,” as a matter of fact, she explained. I couldn’t imagine anyone having any need for two “don’t do poison” posters, so I innocently asked her to help me understand why. I cried as she started to talk.

She said there had been some grumbling; among whom, she was not inclined to say. But some folks seemed to think that I didn’t draw the boy on the poster. They felt like it was a bit too accurate for a six-year-old’s skill. It was a small town; most people knew how my dad could draw. So Mrs. Hughes was bound and determined to prove them wrong. However, I did not want to play. She said I could work on it during school, and she’d be the witness that every line of it was mine. I respectfully declined. I didn’t want to draw anymore. It was hard enough the first time; I was sick and tired of rearranging tiny lead lines. And suddenly it wasn’t much fun to win anymore, either.

But Mrs. Hughes wasn’t having any of it. She handed me the pencil and said, “Draw.” Then she dropped off a box of Kleenex for my snot and went back to the front of the room to teach. I sat on the floor with my blank canvas and the slivers of glass that surround you when your innocence gets smashed. More than anything, I did not want to draw.

Yet I did. Timidly at first, so distracted by the thousands of thoughts darting through my head. Then more focused but mightily frustrated as I fell back into the same ruts of difficulty I got stuck in the first time around. Those arms, and those crossed legs! Yet I drew. . . bravely, almost in defiance of those who had second-guessed. I had something to prove, and I had a dad to protect. My integrity was not on the chopping block alone; his was there, too.

A few days later, when I finally finished the poster, the local paper came to take a picture. Granny curled my bangs and laid out my favorite low-waisted, striped dress and black patent shoes for the occasion. Mrs. Hughes let them take a picture of her and me and the work, but then she demanded that they take one of me on the floor next to the poster with a pencil in my hand. My first grade teacher wanted documentation of what she had watched me do.

I suppose the world was appeased, but it never mattered very much to me after that—the world’s opinion, that is. But I’ll tell you what did matter: the fight in my first grade teacher’s eyes. She hadn’t taken up for me; she had built me a one-way road to take up for myself. By turning my shoulders in the right direction, pushing me forward, and then walking away, she taught me how to be tough. She taught me to hang my hat on what I did, not what others thought about it, good or bad. And she taught me that leaders stand up for what they believe in and fight for the rights of those in their care.

I got a lesson that wasn’t in the textbook. First grade not only prepared me for second, it laid a nonporous foundation for life beyond the fences of a school. It was a gift I tried relentlessly to repay to Lucille Hughes between the day she retired and the day the good Lord came to get her. It never happened, though. The only way to settle a score that fundamental is to pass it on.

P.S. The following is an excerpt from “What Makes a Great Teacher” by Amanda Ripley. The article appeared in “The Atlantic” Jan/Feb 2010. Mr. Taylor’s book, Teaching As Leadership is available on Amazon.