Work Smarter Not Harder

Athletes are creatures of habit. They are drawn like shards of steel are to a horseshoe magnet to things people say they cannot do. It’s part of their unique make up, part of what separates them from the ordinary folks who do not feel the pull. They are all about the hard.

The way they work is influenced by that, too. And it’s not always in the best interest of their prowess. They can get addicted to the grind—as well as to the things that rarely happen…the feat that realistic competition might not ever give them a chance to try. They work and work and work. Sometimes in the wrong ways, sometimes even, on the wrong things.

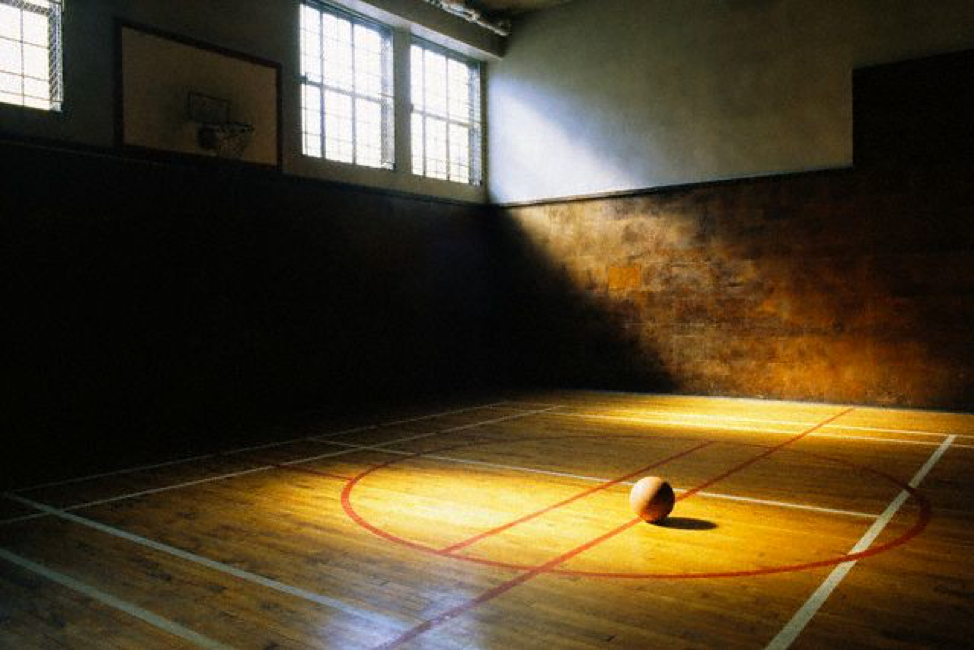

When I was in high school, we got a new coach heading into my senior year. By then I had long had a key to the gym. The custodian was my buddy, the superintendent led singing at my church. I pretty much came and went whenever I wanted, spending way more time sweating than most anyone I knew. Enter a new coach who watched me often through the diamond shaped windows of the old wooden doors.

Athletes can get addicted to the grind, as well as to the thing that rarely happens--the feat of realistic competition might not ever give them a chance to try. They work and work and work. Sometimes in the wrong ways, sometimes even, on the wrong things.

Coach had been at it for a while, this coaching thing. He’d seen a lot in his days sitting just outside the lines. One afternoon while watching me dig myself deeper and deeper in my own hellish hole, he finally intervened. Elvin Sweeten was a big man. His hair was gray and he always thought a lot about the words he was about to say before he decided to say them. He ambled in and spread out in a chair. I was as irritated by his presence as I was at what he didn’t say. He just sat there watching me fight the wind.

Finally, as I punished the ball for missing, my shot getting worse instead of better, Coach asked me if I’d ever sharpened a knife. I looked at him wishing I had one right about then.

Confused, more than a lot irritated and more than a little intrigued, I walked over, grabbing the iron rail behind him by one hand while balancing one foot on top of the ball. I looked at him inquisitively, silently giving him permission to explain. He asked again, “Have you ever sharpened a knife?”.

“No, but it’s obvious that there’s a reason I should have or at least should know how.”

Awkward silence. He was wallowing in his wisdom. Coach always grinned when he got to teach you something you needed to know. Eventually he said, “To make a knife really sharp, you rub it against a hard surface. Over and over and over again. Hard on hard makes a blade so sharp it can split a hair…”

I liked where he was going. My smugness was starting to grow.

Then he said, “However…”. And that’s when things started to go south.

“However, once you get it sharp,” he said, “if you keep on whetting, the blade will actually start to dull. You can only get a knife so sharp.” And then after another awkward silence, he got up and wobbled out as slowly as he had wobbled in.

“However, once you get it sharp,” he said, “if you keep on whetting, the blade will actually start to dull. You can only get a knife so sharp.”

The next day there was a padlock on the gym doors. If I couldn’t do it, he would save me from myself.

Grinding, even when it’s counterproductive, can make an athlete feel like a winner. It’s our proof of life when the ransom comes due. But the real way to get better is to think about what you do and how and why. Find the best way. Do the right stuff. Do the amount that gives you the best chance to improve—find the fulcrum between not sharp and overzealous dull.

Unfortunately, lots of times we don’t want to slow down enough to recognize where the lever needs to turn. We’re too busy working with our head down, earning our badge through grappling because that’s what makes us feel worthy. Except that’s not what the trophy is for—how hard we chase it. The trophy is for being the best. Period. The work matters, without question, but the kind of work matters more. Pete Carril, the legendary Princeton skipper, said the smart take from the strong. They take from workers who work just for the sake of working, too.

Sherri Coale

P.S.