The Accumulation of Time

One year ago, I started my blog, “A Weigh of Life,” with an essay about my Dad. It’s hard to believe that 52 weeks of Tuesday postings have passed since then, and yet that is how time accumulates. A little every day becomes a pile after a bit until suddenly you have something you never could have seen.

It seems only fitting that as this one-year anniversary lines up with Father’s Day, dads should be the subject once again.

I hope you took yours fishing this past weekend. I personally don’t know any who wouldn’t have wanted to go.

…Something happens to a man when a baby comes along. Something happens to everyone remotely connected to the baby when a baby comes along, but the shift that occurs in a dad is palpable. It’s like his skin turns inside out. The tough stuff is still there, it’s just way more concentrated in certain areas and way less all inclusive. Suddenly, there are fissures where things can travel in and out.

Fatherhood affects a man’s eyes, too. What he looks at changes, within seconds, but so does how he sees things when he looks. It’s as if they hand out 3D glasses after delivery, and when he sets his eyes on this tiny human that has his ears and someone else’s nose, he can see the child in the present, and then the future, and then forever in one fell swoop. That’s a lot to process, especially when you feel responsible for all that lies ahead. Unfortunately—or fortunately maybe—depending on how you look at it, the glasses never come off. They come with the goody basket and the baby blanket with the hospital logo stamped in the corner and the sitz bath instructions for mom. They’re part of the package for a dad when he takes his baby home.

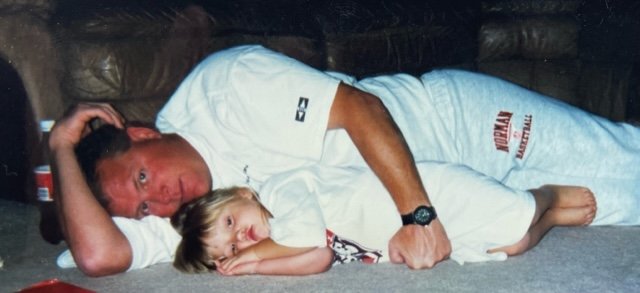

Society tries to tell us that dads should be supermen—as in don the cape and save the day. But super men do a whole lot more than protect and fix and solve. Dads earn their title in the boring everydayness of being around. Not all their jobs are big, bold, and loud. As a matter of fact, most of them aren’t any of those things at all. The malleable little people for whom they are responsible need miniscule nudges, and bumper guards with give, and enough room to find their way. Quiet things that rarely make a scene.

They also need models and directives and pokes and prods and discipline and accountability—all those hard-to-wrap-your-arms-around things that can overwhelm the most diligent and prepared. I’ve always thought in my heart of hearts that’s one of the reasons some dads run. Sheer terror at the thought of all they have to be and do. (They never run for lack of love; you can’t convince me that’s even a thing.) They just can’t see themselves as having all the stuff it takes to wear the title well. I wish they all could know that no one has the stuff. Everybody builds it as they go.

I heard a story once about a woman who lived on an obscure piece of land hidden from public view by a grove of trees. To get to her place you had to know it was there and be willing to go looking to find it. But those who did were always glad they made the trek.

What you’d find once you made your way down the graveled path cut through the undergrowth of unkempt land was a majestic hillside of daffodils in every color under the sun. Five acres of flowers were planted in swaths of cerulean blue and butter yellow, deep orange and vibrant red. The side of the mountain looked as if someone had poured vats of color from the top that had frozen into ribbons of grandeur on their way down. The sight was breathtaking to everyone who viewed it. Word got around fast that it was worth a see.

So, the owner of the property posted a little sign on the front porch of her very modest cabin, the place that she called home. The sign simply read:

“Answers to the Questions I Know You’re Asking”

1. 50,000 bulbs

2. One woman, two hands, very little brain

3. Since 1958

The story is, apparently, true. A little research revealed that it was first told by Jaroldeen Edwards who coined the term, “The Daffodil Principle,” and wrote a book of that same name. Every year—for over 40 years it seems—in the San Bernadino Mountains, Gene Bauer planted daffodils. Edwards told Bauer’s story, then wrote about it, and it’s since been repeated for decades around the world.

I thought of it—and her—this morning as I thought about my dad. And my husband who is a dad. And my son who is a dad. And my friends who are dads. And the young men, who I once taught, who are now dads. And I thought about the dailiness of their charge. The showing up part that refracts continually whether they are conscious of it or not. By how they walk and talk and laugh and think and play and work and pray, they leave pieces of themselves in those they shelter and clothe. The little things add up.

It's the accumulation of time that does the molding. It makes both parties who they are.

I never once found a Father’s Day card that I thought fit my dad. What he’d end up with every year was something supposedly funny about golfing or fishing or farting or picking your nose. My dad wasn’t a “come sit on my knee and let me teach you scripture” kind of dad, but every Sunday you could find him in his pew at church. He wasn’t a lecturer or a sage advice giver or a booming professional success in the way the world hands out its marks, but he taught me how to swing a club and a bat and how to plant a tree and edge a lawn and draw letters flawlessly to scale. He loved me and my brother unabashedly and he did the father thing the best that he knew how. His try was perfectly imperfect—it gave us both room to become.

I hope dads get the fact that the simple wonder of their love and presence has mystical powers that make up for all they don’t know how to do. Sometimes in their urgency (egged on by the world) to be all things grand and emphatic to their children, they undervalue the shaping power of uncomplicated, bottomless love. It takes neither talent nor education to wrap a child up in agape. The accumulation of days spent doing that will take care of all the rest.

Sherri Coale

P.S.