Messy Margins

The lady at the airport bookstore in Denver wasn’t wrong. But she wasn’t right either. She said people shouldn’t write in the margins of books. She said books were made to be read-- not written in-- and that marking them up lowered their value. This was information she chose to volunteer as I prepared to take a chance on a New York Times best seller from the display in the front and a random collection of essays I found hiding behind the journals on a crowded shelf in the back. “As a matter of fact,” the chatty salesclerk added, “books that have been written in, cannot be returned and exchanged as part of the bookstore’s share program.” A truth that followed an opinion as it came to her stance on books.

I hadn’t inquired about either, and yet, there both were in my lap.

While I appreciated the side window the jabbering clerk came in through to introduce the store’s book share program, I would not be exchanging my purchases, regardless of how they might or might not move me, and I did not share her stance on books. Good books, for me, are like velveteen rabbits. Their value shows up in their wear.

For as long as I can remember, I have written in the margins of my books. I read with a highlighter in hand and an ink pen nearby. I draw stars and exclamation marks and parenthetical brackets. I write words like “WOW” and “Amen” and “Bingo” in the margins that flank the author’s text. I do it in novels, memoirs, essays, short stories, screenplays, poetry, non-fiction how-to’s. Genre doesn’t dictate. I dog ear passages that make me think, lines I want to remember, sentences that clip-clop like the hooves of horses on the street. My mark-ups in the margins are for both style, the writer’s art, and also for content, the substance it houses. I highlight things I want to remember. Things I can’t afford to forget. Sentences I want to be able to find again. Paragraphs that make me itch. Passages that can serve as B-12 snacks when I only have a minute and want to sit in something good.

But the doodling provides, in retrospect, even more than that. The running commentary peppered throughout the texts of my books serves as little landmarks for the stories of my days. When I pull one from my shelves and thumb back through, I can feel where I was when I read it first. What problem I was trying to solve. What skill or attribute I was working to forge. What season of life I was in. I can look backward down the looking glass to see both who I was and who I was trying hard to be. In a way, the messy margins serve as footnotes for my life.

For instance, when I pick up Doctors, by Erich Segal, I think of a schoolteacher summer in the early years of married life—those wildly confident, anticipatory years between college and kids, the days that burst at the seams with independence and the sweet innocence that comes from not knowing what you cannot yet know. I devoured Segal’s book one summer—all 679 pages of it. It sits on my shelf now, thicker than it once was, as the pages lay wavy from the sprinkler and the sun. Doctors was a novel exploding with medical terms that I had to look up constantly to understand, but I loved the characters and the intertwined plot and the arc of the story. And when I catch it out of the corner of my eye, posted up in its spot on my shelf, I remember me then, running toward a life I was bound and determined to make.

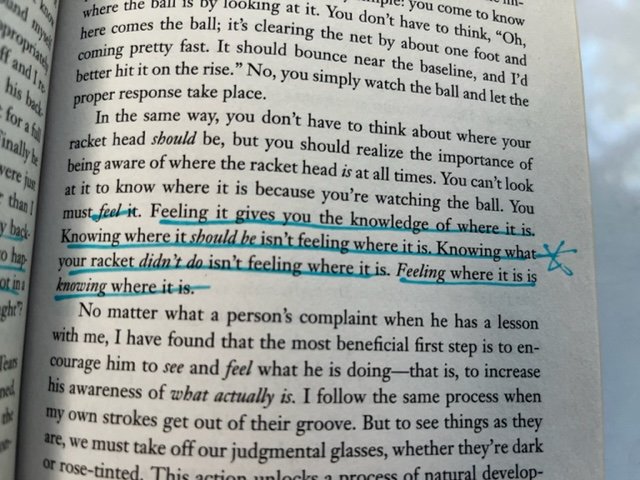

Similar romps happen when I pick up In Pursuit of Wow and The Inner Game of Tennis and Pat Conroy’s Prince of Tides. I was building a program. I was grappling with how to better teach. I was escaping from all that was pulling at me through the glorious storytelling of a writer who knew how to take me places I could not otherwise go. Who I was at each of those junctures is palpable when I turn to the dog-eared pages and read the underlined text. Each and every book that touched me houses a version of me at a given moment in time. It’s like a roadmap for a path made by walking. It makes some sense when I look back.

Years in the future when I thumb through These Precious Days by Ann Patchett, I will see the illegible pink smears of highlighter-- efforts of a free, non-dominant hand trying to earmark a passage--and I will remember rocking my granddaughter for a nap when she was one. I will remember that Amazon dropped Patchett’s new book at my door and that I couldn’t wait to lap it up, so I sat it on the table next to the rocker where I could read it while Austyn slept. And I know, because of what the books on my shelves have taught me, that I will be able to feel those two birds in my soul at once—the words that grabbed me at first blush and my granddaughter fast asleep. The two will be inextricably linked. I’ll reach for Patchett when I want to remember how it felt to hold Austyn in my arms.

Writing in the margins of a book might lower the book’s value. It might disqualify it from ever being a participant in an exchange program or part of a loaner library system. And It might be heresy to highbrow collectors, as well as those who just like the look of books. But I need a book to be lived in. Like the stuffed animal with all the hair rubbed off and an eyeball hanging by a string, my books mean the most to me when they sit on my shelf well-worn.